Help our mission to provide free history education to the world! Please donate and contribute to covering our server costs in 2024. With your support, millions of people learn about history entirely for free every month.

$ 15692 / $ 18000

The was an act of political protest carried out by American colonists on 16 December 1773, in Boston, Massachusetts. Disguised as Mohawk Native Americans, the colonists dumped 342 crates of tea into Boston Harbor to protest both a tax on tea and the monopoly of the British East India Company on the tea trade.

The Boston Tea Party was part of a broader dispute between the Parliament of Great Britain and the Thirteen Colonies of British North America over Parliament's right to tax the colonies; the colonists argued that any attempt made by Parliament to directly tax them violated their constitutional rights as Englishmen since they were not represented in Parliament. In May 1773, Parliament passed the Tea Act which was supposed to bail out the financially troubled East India Company by giving it a monopoly on the tea trade in America. The colonists interpreted this as another attempt to dominate them and resolved to stop the tea from being unloaded. After the destruction of the East India Company tea, Parliament decided to punish Boston and issued a series of punitive acts in early 1774 known collectively as the 'Intolerable Acts'; the passage of these acts helped spark the American Revolutionary War (1775-1783). The Boston Tea Party remains one of the most iconic episodes of the American Revolution (c. 1765-1789).

AdvertisementIn the mid-1760s, the Parliament of Great Britain needed fresh sources of tax revenue to pay off the massive amount of debt it had accrued fighting the recent Seven Years' War (1756-1763). One potential source was the Thirteen Colonies of British North America, in whose defense the war had partially been fought. Believing that the colonies should help shoulder the financial burden of the British Empire, Parliament passed the Stamp Act in March 1765, which placed a tax on all paper materials in the American colonies including newspapers, legal documents, calendars, playing cards, and more. The Stamp Act was met with vehement resistance from the colonists, who believed that such a tax violated their rights as Englishmen, specifically the right of self-taxation. Since the Americans were unrepresented in Parliament, they contended that Parliament had no power to directly tax them.

Protests erupted across the colonies & American merchants put economic pressure on Britain by boycotting British imports.

Such sentiments were reiterated by the colonial assemblies, including Virginia's House of Burgesses, which issued a series of resolves asserting that only Virginia had the power to tax Virginians. Protests erupted across the colonies; while American merchants put economic pressure on Britain by boycotting British imports, other colonists took to the streets. On 14 August 1765, a mob gathered in Boston, capital of the Province of Massachusetts Bay. It hung an effigy of the colony's stamp distributor from an elm tree before ransacking his home. Twelve days later, the mob stormed the house of Lieutenant Governor Thomas Hutchinson of Massachusetts, forcing him and his family to flee to Castle Island in Boston Harbor. These riots gave rise to the Sons of Liberty, a loose organization of underground American political agitators.

AdvertisementIn the face of these hostile reactions, Parliament rescinded the Stamp Act in early 1766. However, the colonists barely had time to celebrate before Parliament passed a new set of taxes and regulations, known collectively as the Townshend Acts, in 1767 and 1768. Again, the colonies erupted in protest; the Massachusetts House of Representatives passed a circular letter to its fellow colonial assemblies urging them to petition the king against the taxes, while colonial merchants entered into new nonimportation agreements on British goods. The epicenter of American defiance was once again in Boston, where a mob took to the streets in June 1768 to beat up tax collectors. The situation in Boston became so unstable that General Thomas Gage, commander-in-chief of all British forces in North America, sent in 2,000 soldiers to keep the peace in October 1768. Tensions culminated in the Boston Massacre when nine British soldiers fired on a mob of Bostonians on 5 March 1770; eleven men were hit, five of whom ultimately died.

About a month after the massacre, Parliament repealed most of the Townshend Acts; the new British Prime Minister, Lord North, wanted to ease tensions in North America so he could focus his attention on other matters across the vast British Empire. Although most of the taxes were rescinded, Lord North kept the tax on tea in place for several reasons. First, Parliament wanted to make it known that it was not conceding its authority to tax the colonies; by keeping at least one of the Townshend taxes in place, Parliament was signaling that the argument was not yet over. Second, Parliament decided that from now on, the salaries of colonial officials would be paid from the revenue of the tea tax; this would keep the officials dependent on Parliament and ensure that they would be less likely to be swayed by pressure from the colonists.

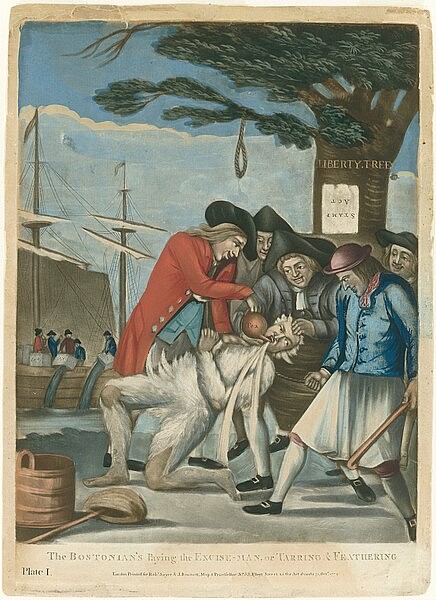

AdvertisementAfter this partial repeal of the Townshend Acts, a period of relative political calm descended on the colonies. This calm was by no means total; the scars left by the Boston Massacre still ran deep, dividing Americans who considered themselves 'Loyalists', or supporters of Britain, from those who considered themselves 'Patriots', or opponents of the Parliamentary taxes. Colonial assemblies still quarreled with their governors, Sons of Liberty still occasionally tarred and feathered Loyalists, and a group of Rhode Islanders seized and burned a Royal Navy schooner, HMS Gaspee, in June 1772. However, despite isolated incidents like the Gaspee Affair, it seemed that Lord North's attempts to ease tensions in North America were succeeding. The colonial merchants had given up their nonimportation agreements and the British soldiers who had perpetrated the Boston Massacre had been tried and mostly acquitted, leaving many to hope that relations between Britain and its colonies would soon improve.

Such hopes would evaporate after 10 May 1773, when Parliament passed the Tea Act. Unlike the Stamp Act and Townshend Acts before it, the Tea Act was not meant primarily to tax or punish the Americans. Rather, it was intended to bail out the British East India Company, one of Britain's most crucial commercial institutions, which was teetering on the edge of bankruptcy after experiencing financial setbacks in India. Many in Parliament saw the salvation of the East India Company in its surplus of tea; although the company was having difficulty selling the tea in European markets, there was enough of the commodity in the company's inventory to rescue it from collapse, if only a buyer could be found. Parliament's solution was to grant the company a monopoly on the tea trade in the North American colonies. The monopoly was granted at a reduced price, as an incentive for Americans to purchase the legal East India Company tea rather than smuggled Dutch tea, which was being illegally sold by colonial merchants. Consequentially, Parliament decided to retain the tea tax that had initially been imposed in 1767; at only three pence per pound, no one ever thought the colonists would put up much of a fuss, considering the tea would be much cheaper than any alternative even with the tax.

The colonists, however, saw things differently. Rather than a simple effort by Parliament to bail out the East India Company, they viewed it as another attempt to dominate them. Samuel Adams (1722-1803), a Bostonian who was already well-known as an outspoken opponent of taxation without representation, condemned the East India Company's monopoly as a 'poison'; he and other like-minded figures pointed out that, by purchasing the East India Company's cheap tea, the colonists would also be paying Parliament's tea tax, which would amount to an acknowledgment of Parliament's authority to tax them. In the words of Adams' biographer Stacy Schiff, it seemed as though Parliament "could literally slip British sovereignty into the drinking water" (230). For this reason, when news of the Tea Act arrived in the colonies in September 1773, the outrage that had lain dormant for the last three years was reignited.

AdvertisementShortly after they first learned of the passage of the Tea Act, the colonists received news that seven ships carrying East India Company tea were already bound for the colonies: four were sailing for Boston, and one each for Philadelphia, New York, and Charleston. In each of these towns, the East India Company had appointed American merchants to act as consignees; these merchants would receive the tea from the East India Company and sell it for them in return for a commission. Before the tea had even arrived in the colonies, the Sons of Liberty directed colonial anger toward these consignees. On 16 October 1773 in Philadelphia, the Sons of Liberty hosted a meeting during which it was decided that anyone importing East India Company tea was to be branded "an enemy to his country", and a committee was appointed to demand the resignations of the consignees (Middlekauff, 228). By December, all Philadelphian consignees had resigned; these decisions were heavily influenced by threats from groups of Patriots like the unsubtly named "Committee for Tarring and Feathering". Therefore, when the ship carrying the East India Company tea arrived in Philadelphia, there was no one to receive it, forcing the ship to return to Britain with its unsold cargo.

Similarly, the Sons of Liberty in New York intimidated their consignees into resigning. The governor of New York attempted to fight back, demanding that when the tea arrived it would be unloaded regardless, and a nearby British warship was poised to enforce this decree. However, the cargo ship never arrived; damaged by a storm and forced to seek repairs, it arrived in New York much too late and was forced to sail for England, having never unloaded its tea. The ship bound for Charleston, South Carolina, made it safely to its destination but had to wait in the harbor since all the Charleston consignees had resigned. After 20 days, South Carolina's governor legally seized the tea, since the ship had been unable to pay the importation duties. The cargo was then stored away and never sold. In three of the four colonial towns, therefore, the protesting Americans had made their voices heard. But, once again, it was in Boston where the most dramatic and significant of these protests would occur.

Even before news of the Tea Act broke, trouble was stirring in Boston. In August 1772, Massachusetts learned that the salaries of its judges would now be paid out of the tea tax revenue, thereby placing the colony's judiciary outside the sphere of public influence. Worried that more colonial officials were becoming beholden to the Crown rather than to the people of Massachusetts, Samuel Adams and his allies called for the establishment of a committee to state the rights of the colonies. This committee met in November 1772 and produced a document in which it affirmed the natural rights of the colonists and condemned the Crown salaries for judges as the latest in a long list of "infringements and violations" of those rights (Schiff, 218). This document, known as the 'Boston Pamphlet', was co-authored by Adams and some of Boston's leading Patriots including James Otis, Jr., Josiah Quincy, Jr., and Dr. Joseph Warren.

AdvertisementThis Boston Pamphlet was opposed by Thomas Hutchinson, now governor of Massachusetts. In January 1773, he gave a speech in which he argued that the colonists enjoyed some rights of Englishmen but not all and that the colonies had been subservient to Parliament since their founding. Adams and his allies responded to this attack in June, when they published Hutchinson's personal letters, which had been supplied to them six months earlier by Benjamin Franklin (1706-1790). The letters revealed the frustration of Hutchinson and other royal officials over the recent opposition in the colonies; while this was hardly surprising, the timing of the letters' publication only seemed to emphasize the point that Britain's officials were alienated from the colonists. Some Americans even interpreted the letters as evidence that a conspiracy existed to deprive them of their rights.

Unable to unload the tea or sail away; all the Dartmouth could do was await the payment deadline & see how events played out.

So, by the time Boston learned that four ships laden with East India Company tea were on their way, tensions were already high. Adams' faction of Patriots tried their best to compel Boston's consignees to resign as had happened in Philadelphia, New York, and Charleston. Governor Hutchinson, eager to reassert his authority, persuaded the consignees (two of whom were his sons) to stand their ground. No amount of intimidation from the Sons of Liberty was sufficient to force their resignations, leading to something of a standoff on 28 November 1773, when the first of the ships carrying tea, the Dartmouth, arrived in Boston Harbor. According to British law, Dartmouth had 20 days to unload its cargo and pay the necessary import duties before the goods became liable to be seized and auctioned off by customs officials. In this case, the deadline was midnight on 17 December. On 29 November, Adams invited "every friend to his country, to himself, and posterity" to attend a meeting at Boston's Faneuil Hall to discuss how to best face this threat to American liberty (Schiff, 234). As it happened, Adams' meeting was attended by 5,000 Bostonians (out of a total population of 16,000); the venue had to be changed to the Old South Meeting House, as Faneuil Hall proved too small.

Adams insisted that the tea must be rejected and informed Francis Rotch, the young Nantucket merchant who owned Dartmouth, that the cargo must be returned to England; any attempt to unload the tea would be resisted. The meeting also decided to post a 25-man guard to watch Dartmouth to ensure that none of the ship's 114 crates of tea left the cargo hold. Governor Hutchinson retaliated by forbidding Dartmouth from leaving Boston Harbor until it had paid the necessary duties. Rotch and the ship's captain were therefore caught in a bind, unable to unload the tea or sail away; all they could do was await the payment deadline and see how events played out.

At 10 a.m. on 16 December 1773, Samuel Adams summoned another meeting at Old South Meeting House. Like the 29 November meeting, this one was attended by a sizable portion of Boston's population; the Bostonians likely strained to hear Adams' voice over the cold December rain that fell outside. With less than 14 hours until customs officials could legally seize the tea, Adams asked Rotch to make a last-minute appeal to Governor Hutchinson to be allowed to leave. Rotch did so, returning to the Old South Meeting House at around 6 p.m. to report that his request had been denied; when asked if he would unload the tea, Rotch replied that he would, but only if customs officials compelled him to do so. Adams then rose to thank Rotch for his efforts, announcing that those attending the meeting had "done all they could for the salvation of their country" (Schiff, 240).

About 15 minutes later, war whoops and whistles could be heard from the darkened street outside the meeting house. The crowd slowly began to filter outside, despite calls from Adams and John Hancock for the meeting to remain in session. Some of those who left walked along the waterfront to Griffin's Wharf; by now, Dartmouth had been joined by the Eleanor and the Beaver, two of the other ships carrying East India Company tea. It was at this point that between 30 and 130 men, some of them dressed as Mohawk Native Americans, climbed aboard the ships. In full sight of the gathered crowd, the men dragged the crates of tea on deck, smashed them open, and dumped their contents into Boston Harbor. Before long, all 342 crates had been destroyed; this amounted to 92,000 pounds of tea, worth roughly £10,000. Before anyone could stop them, the perpetrators of the Boston Tea Party melted back into the crowd.

Contrary to popular belief, Samuel Adams likely did not give the signal for the destruction of the tea. However, he immediately worked to publicize the Boston Tea Party and to defend it, emphasizing that it was not the work of a mindless mob but an act of political protest. As word of the protest spread, many Patriot leaders publicly announced support, although some were secretly uncomfortable with the destruction of private property. In the months after the Boston Tea Party, similar acts were carried out. The seventh ship carrying East India Company tea had run aground at Cape Cod, Massachusetts, in December 1773. Its tea was taxed and sold off. In March 1774, the Sons of Liberty learned that this tea was being held in a Boston warehouse; they stormed the warehouse, once again dressed as Mohawks, and destroyed all they could find. In October 1774, colonists in Annapolis, Maryland, were inspired by the Boston Tea Party to burn the Peggy Stewart, a cargo vessel.

Love History?Sign up for our free weekly email newsletter!

In London, news of the Boston Tea Party was met with anger; even those members of Parliament who had previously defended the colonies believed that the Americans had gone too far. Though Lord North was usually a moderate when it came to colonial affairs, he felt that Parliament could not allow the destruction of East India Company property to go unpunished. In early 1774, Parliament passed a series of acts that became known in the colonies as the 'Intolerable Acts', which included the closure of Boston's port until the East India Company was repaid in full for the destroyed tea. Although the Intolerable Acts primarily targeted Boston, they would spark outrage across the colonies and would become one of the direct causes of the American Revolutionary War.