Education has long been recognized as a primary means of improving one’s economic prospects. Today, a postsecondary degree or certificate has become increasingly necessary for earning a middle-class living. The last two decades have greatly heightened the demand for a highly educated workforce—and the earnings differential between those with and without college degrees has widened substantially. A worker with a bachelor’s degree now earns about 66 percent more than a worker with only a high school diploma.1 Over a lifetime, that wage gap will add up to over $1,000,000. At the same time, a college education has become more difficult for students from modest backgrounds to afford.

The rising cost of higher education is a problem in and of itself – and colleges and universities must act to keep their tuition in check. But students are also hindered by the way student aid is allocated. Over the last 20 years, federal financial aid has steadily shifted away from grant-based aid to a predominantly loan-based system. As a result, borrowing has become the most common way for students to finance their education. In 2009, the average graduating college senior from a four-year institution was saddled with $24,000 in debt, a number that has been rising steadily.2 This works out to a monthly payment of $276, or 9.5 percent of the typical graduate’s income. Yet repaying student loans will be even more difficult for many graduates given that the unemployment rate for young degree-holders soared to 8.7 percent in 2009.3 The picture is still darker for students who left school without completing a degree – of the students who entered college in 2003 (the most recent year for which data is available), 31 percent of those with student loan debt in excess of $22,000 had not earned a degree six years later.4 The student loan burden is taking a toll on young adults’ lives: almost 1 in 5 significantly changed their career plans because of student loans; nearly 40 percent delayed buying a home and just over 20 percent reported their debt burden caused them to delay having children.5

The major reason for lower enrollments in 4-year institutions among qualified students from low-income families is the level of unmet need they face in attending college. Unmet need is the amount needed to cover expenses after all loans, grants and work study wages are accounted for. On average, the annual unmet need of low-income families has reached historic levels. In academic year 2007-08, the average low-income family faced $6,480 in unmet need for a public 2-year institution; $9,030 for a public 4-year institution; and $10,400 for a private non-profit 4-year institution.6 Unmet need has forced low- and moderate-income students to abandon the most successful recipe for obtaining a college degree: full-time, on-campus study.

As a result of unmet need, the highest achieving students from poor backgrounds attend college at the same rate as the lowest achieving students from wealthy backgrounds. Or to put it more coarsely: the least bright wealthy kids attend college at the same rate as the smartest poor kids.

A four-year college degree is not the only way to achieve a middle class standard of living: associates degrees and one- and two-year credentials, especially in high-demand fields like engineering and health care, can also represent a path to economic prosperity, in some cases opening the door to earnings that outpace the salaries of some bachelors degree holders.7 The Contract for College would not only provide grant and loan assistance to community college students, but would strengthen the nation’s network of open-enrollment community colleges by reviving President Obama’s plan for the American Graduation Initiative, investing $12 billion in community colleges over the next decade with the aim of producing 5 million additional community college graduates.

Finally, the Contract for College expands college access for one particularly disadvantaged group of students: young people who have grown up in the United States and flourished academically at American high schools but do not have legal immigration status because of immigration decisions made by their parents, often when they were small children. An estimated 65,000 unauthorized immigrant students graduate from high school every year.8 They are excluded from most scholarships, are barred from receiving federal financial aid, and cannot work legally to pay for college. Even a college degree will not guarantee them the opportunity to enter the legal workforce. Instead of making these young people a part of our future middle class, the nation squanders the talent and ability of unauthorized immigrant students by forcing them to remain in the shadows. The Contract for College includes provisions similar to the proposed federal DREAM Act which would offer a path to citizenship to unauthorized students who complete high school and agree to attend college.

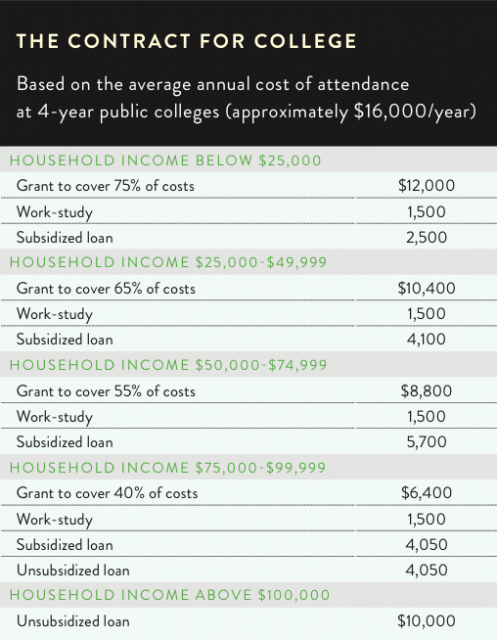

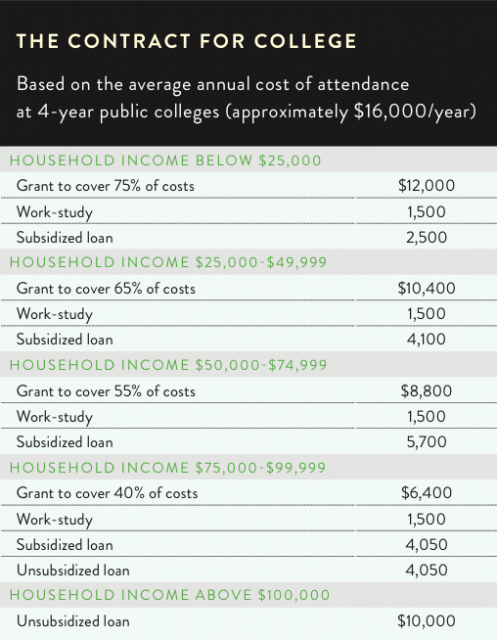

The Contract for College would unify existing strands of federal financial aid – grants, loans and work-study – into a coherent, guaranteed financial aid package for students.9 Grants would make up the bulk of aid for students from low- and moderate-income families. The Contract will recognize the important value of reciprocity – so part of the Contract for every student will include some amount of student loan aid and/or work-study requirement. The Contract is designed to reorient federal aid back to a more grant-based system and ensure that students from all financial backgrounds have upfront knowledge and understanding of the amount and type of financial aid that will be available during their entire course of study. The Contract also provides direct federal investment in community colleges to fund the President’s American Graduation Initiative and offers temporary legal immigration status and path to citizenship for unauthorized immigrants who came to the U.S. as children and plan to attend college.

The key design elements to the Contract for College are featured below, including how existing federal policy and programs will be refashioned under the Contract system.

While each student’s final Contract will be based on the institution costs where the student chooses to enroll, we can use the average cost of attendance for 4-year colleges to model the type of aid students at different income levels will receive under the Contract. According to the College Board, the average total cost of attendance for one year at a public 4-year university was $16,140 for the 2010-2011 school year.10 This cost includes tuition, room and board, books and transportation.

The model below is for illustrative purposes. An actual plan would include more gradual phase-outs between each successive income level. It would also incorporate the likely grants by employers or NGOs and government matches, which are difficult to anticipate at this point.